Keeping Juneteenth Alive in the Archives: Part 1 of 2

By Rebecca Hankins | 06-14-2021

Juneteenth, also called Freedom Day, is the combining of June and the 19th day, and commemorates the day enslaved Africans were freed in Texas on June 19th, 1865. Texas maintains the shameful distinction of being the last of the ten Confederate states to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation. Juneteenth is celebrated in the State of Texas as the day the last enslaved Africans were freed, two years and six months after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation (January 1, 1863). Archives seek to keep the story and memory of this historic event alive.

Historians have noted that the Emancipation Proclamation was not enforced, because at the time of Lincoln’s signing, there were no Union soldiers in Texas to enforce the order. Many of the white slave owners from other slave-owning states fled to Texas in the hopes of using it as a sanctuary and garrison against the Union, where they could maintain their slaveholding status. On June 18, Union Army General Gordon Granger arrived at Galveston Island with 2,000 federal troops to occupy Texas on behalf of the federal government. On June 19, the proclamation titled General Order Number 3 (https://www.archives.gov/news/articles/juneteenth-original-document) was read by General Granger:

“The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired laborer.”

Stories are told of freed people wearing their best clothes and walking everywhere so they could be seen as free. Many left their plantations as a symbol of their freedom. Others traveled to nearby states attempting to find family members sold away. Many of the freed enslaved men and women claimed land, left after slave owners abandoned them to the Union Army. The newly freed celebrated by dragging their former slave cabins away from the slave quarters and into their own fields. Women reduced their labor in the fields and could now devote more time to childcare and their own homes. Now families could work for their own prosperity and livelihoods. It was a time of celebration and uncertainty. The election of Andrew Johnson as President, himself a former slave owner, changed the trajectory of the freed men and women, in particular after he restored many of the liberated lands to the former slave owners. This led many freed people to enter into sharecropping and other forms of servitude to former masters, which inevitably caused them to lose their land and independence.

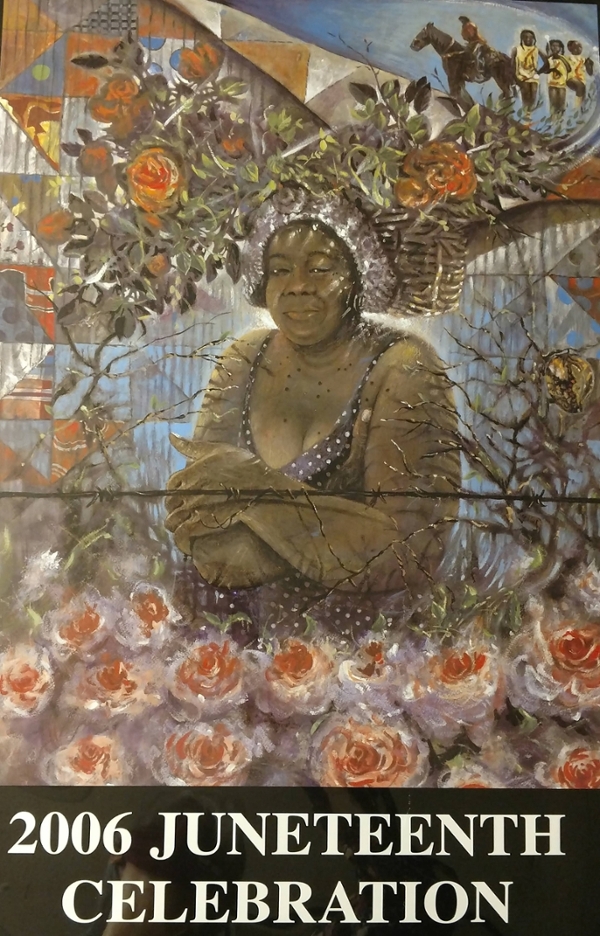

Juneteenth is viewed as a Texas-centered event and there are some that jealously guard this celebration as a uniquely Black Texas holiday. For years, African Americans celebrated Juneteenth by returning to Galveston, Texas as an annual pilgrimage to the place where they first learned of their freedom. They went to share prayer, food, commemoration, and celebration. From 1865 onward, Texas towns and cities adopted the annual celebration in identical ways. African American Former Texas State Representative Al Edwards, who was born in Houston in 1937 and first elected as a state representative in 1978, began the crusade to acknowledge Juneteenth. A year later, in 1979, Edwards authored and sponsored House Bill 1016, making June 19th (“Juneteenth”) an official paid state holiday in Texas, although it is not a Federal holiday. Representative Edward successfully spread the observance of Juneteenth across America until his death on April 29, 2020.

Learn more about Juneteenth and Cushing Memorial Library and Archives resources by reading Part 2 of this essay. (Keeping Juneteenth Alive in the Archives: Part 2 of 2)

Tags: Juneteenth; African Americans; Texas; Civil War; Confederacy.

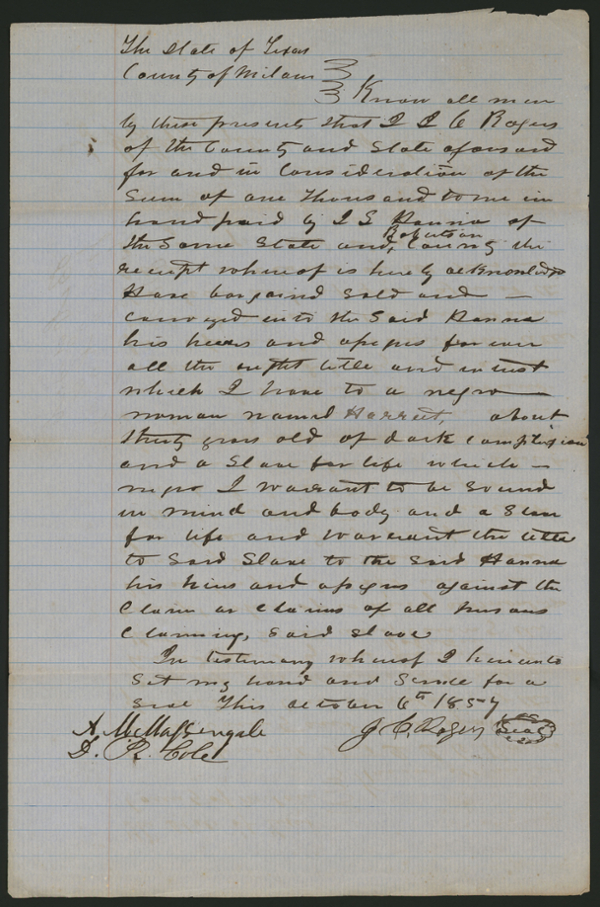

Cushing Memorial Library and Archives Collections: Africana Studies; Floyd & Louise Chapman Texas & Borderlands Collection; University Archives; Ku Klux Klan Collection (American Nativism); Charles Criner Papers and Art Collection; Clyde McQueen Collection, 1944-1999; Slavery and Emancipation Documents; William Harrison Mays Collection; TAMU Yearbooks

Contact Us: cushingcollective@library.tamu.edu

|

Rebecca Hankins is Professor, librarian, and certified archivist at Texas A&M University. She is an affiliated faculty in Interdisciplinary Critical Studies that include Africana Studies, Women’s & Gender, and Religious Studies. Hankins’ research and scholarship fits within a broader discourse on African American Muslims’ religious identity and new media. |